FRAMING SOCIETY

By John Head

Social Register Observer

Winter 2001

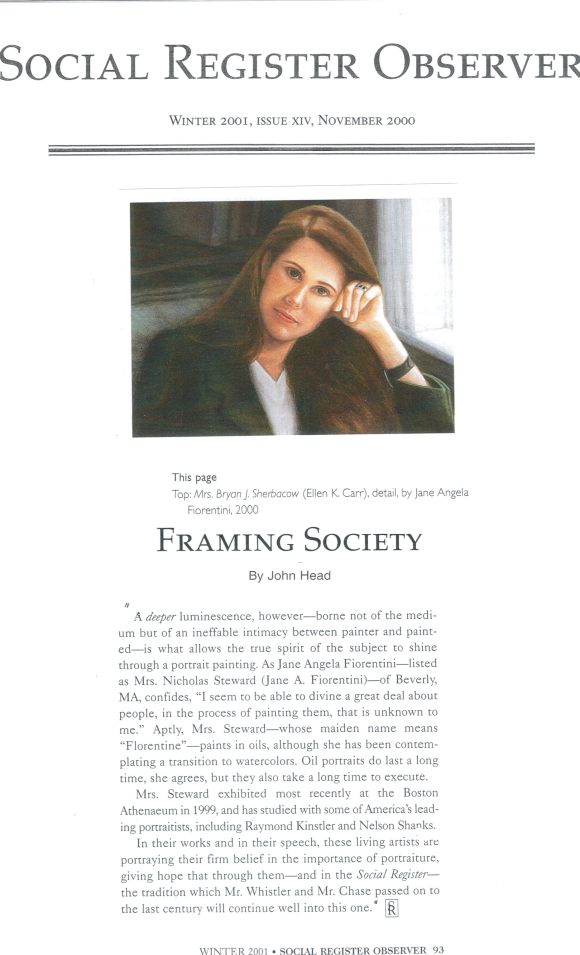

A deeper luminescence, however—borne not of the medium but of an ineffable intimacy between painter and paint-ed—is what allows the true spirit of the subject to shine through a portrait painting. As Jane Angela Fiorentini—listed as Mrs. Nicholas Steward (Jane A. Fiorentini)—of Beverly, MA, confides, “I seem to be able to divine a great deal about people, in the process of painting them, that is unknown to me.” Aptly, Mrs. Steward—whose maiden name means “Florentine”—paints in oils, although she has been contemplating a transition to watercolors. Oil portraits do last a long time, she agrees, but they also take a long time to execute.

Mrs. Steward exhibited most recently at the Boston Athenaeum in 1999, and has studied with some of America’s leading portraitists, including Raymond Kinstler and Nelson Shanks.

In their works and in their speech, these living artists are portraying their firm belief in the importance of portraiture, giving hope that through them—and in the Social Register—the tradition which Mr. Whistler and Mr. Chase passed on to the last century will continue well into this one.”

Artist sets up studio in downtown Haverhill

By TOM VARTABEDIAN

Gazette Staff Writer

March 31, 1989

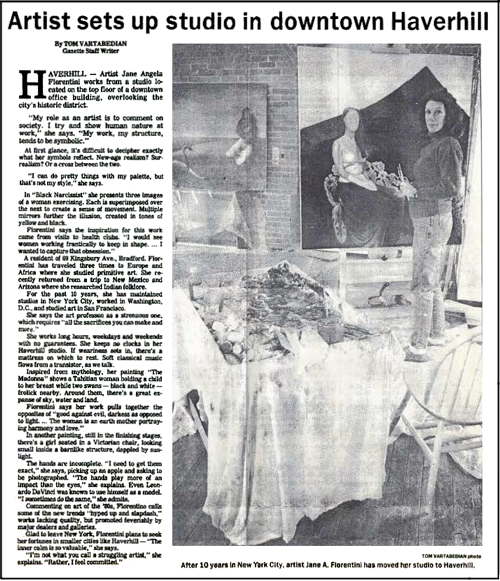

HAVERHILL -Artist Jane Angela Fiorentini works from a studio located on the top floor of a downtown office building, overlooking the city’s historic district.

“My role as an artist is to comment on society. I try and show human nature at work,” she says. “My work, my structure, tends to be symbolic.”

At first glance, it’s difficult to decipher exactly what her symbols reflect. New-age realism? Sur-realism? Or a cross between the two.

“I can do pretty things with my palette, but that’s not my style;” she says.

In one painting she presents three images of a woman exercising. Each is superimposed over the next to create a sense of movement. Multiple mirrors further the illusion, created in tones of yellow and black.

Fiorentini says the inspiration for this work came from visits to health clubs. “I would see women working frantically to keep in shape. . . . I wanted to capture that obsession.”

A resident of Bradford, MA Fiorentini has traveled three times to Europe and Africa where she studied primitive art. She recently returned from a trip to New Mexico and Arizona where she researched Indian folklore.

For the past 10 years, she has maintained studios in New York City, worked in Washington, D.C., and studied art in San Francisco.

She says the art profession as a strenuous one, which requires “all the sacrifices you can make and more.”

She works long hours, weekdays and weekends with no guarantees. She keeps no clocks in her Haverhill studio. If weariness sets in, there’s a mattress on which to rest. Soft classical music flows as we talk.

Inspired from mythology, her painting “The Madonna” shows a Tahitian woman holding a child to her breast while two swans–black and white–frolic nearby. Around them, there’s a great expanse of sky, water and land.

Fiorentini says her work pulls together the opposites of ”good against evil, darkness as opposed to light … The woman is an earth mother portraying harmony and love.”

In another painting, still in the finishing stages, there’s a girl seated in a Victorian chair, looking small inside a barn-like structure, dappled by sun-light.

The hands are incomplete. “I need to get them exact,” she says, picking up an apple and asking to be photographed. “The hands play as much of an impact as the eyes,” she explains. Even Leonardo Da Vinci was known to use himself as a model. “I sometimes do the same,” she admits.

Commenting on art of the ’80s, Fiorentini calls some of the new trends “hyped up and slapdash,” works lacking quality, but promoted feverishly by major dealers and galleries. Glad to leave New York, Fiorentini plans to seek her fortunes in smaller cities like Haverhill. “The inner calm is so valuable,” she says. “I’m not what you call a struggling artist,” she explains. “Rather, feel committed.”